Issue #3: The Past, Present, and Future Apocalypse

What comes to mind when you picture the Apocalypse? A lifeless, irradiated planet? The end of times from religious texts? What did our ancestors imagine and experience? What about our future selves or our descendants?

What comes to mind when you picture the Apocalypse? A lifeless, irradiated planet? The end of times from religious texts? What did our ancestors imagine and experience? What about our future selves or our descendants?

Did the inhabitants of Italy who lived through the fall of the Roman Empire to the "barbarians" experience an apocalypse? Would the survivors of the bubonic plague of the dark ages have any reason to think the world was not ending? What about the desolate, irradiated and ghostly remnants of Pripyat, Ukraine caused by the Chernobyl disaster? Or the ongoing wars in Syria, Ethiopia and Ukraine that have turned entire towns and cities into ghost towns filled with rubble?

We as a species have experienced (and will continue to experience) many apocalypses. Historian, author, and podcaster, Dan Carlin, demonstrates how society is both paradoxically resilient and immensely fragile in his book, The End Is Always Near: Apocalyptic Moments, from the Bronze Age Collapse to Nuclear Near Misses. Apocalypses are largely a matter of perspective and context, Carlin writes:

“Since human civilization first arose, societies have “risen” and “fallen,” “advanced” and “declined”—or so the histories written decades ago often said. More commonly now, historians refer to societies in “transition,” rather than use terms that denote forward or backward development. Continuity, too, is often emphasized, instead of the emphasis found in earlier historical accounts of hard breaks from a previous era...

So, did the Roman Empire “fall” to the “barbarians,” or did it transition to an equal yet more decentralized era, one with a more Germanic flair?”

The Past Feels Like The Present

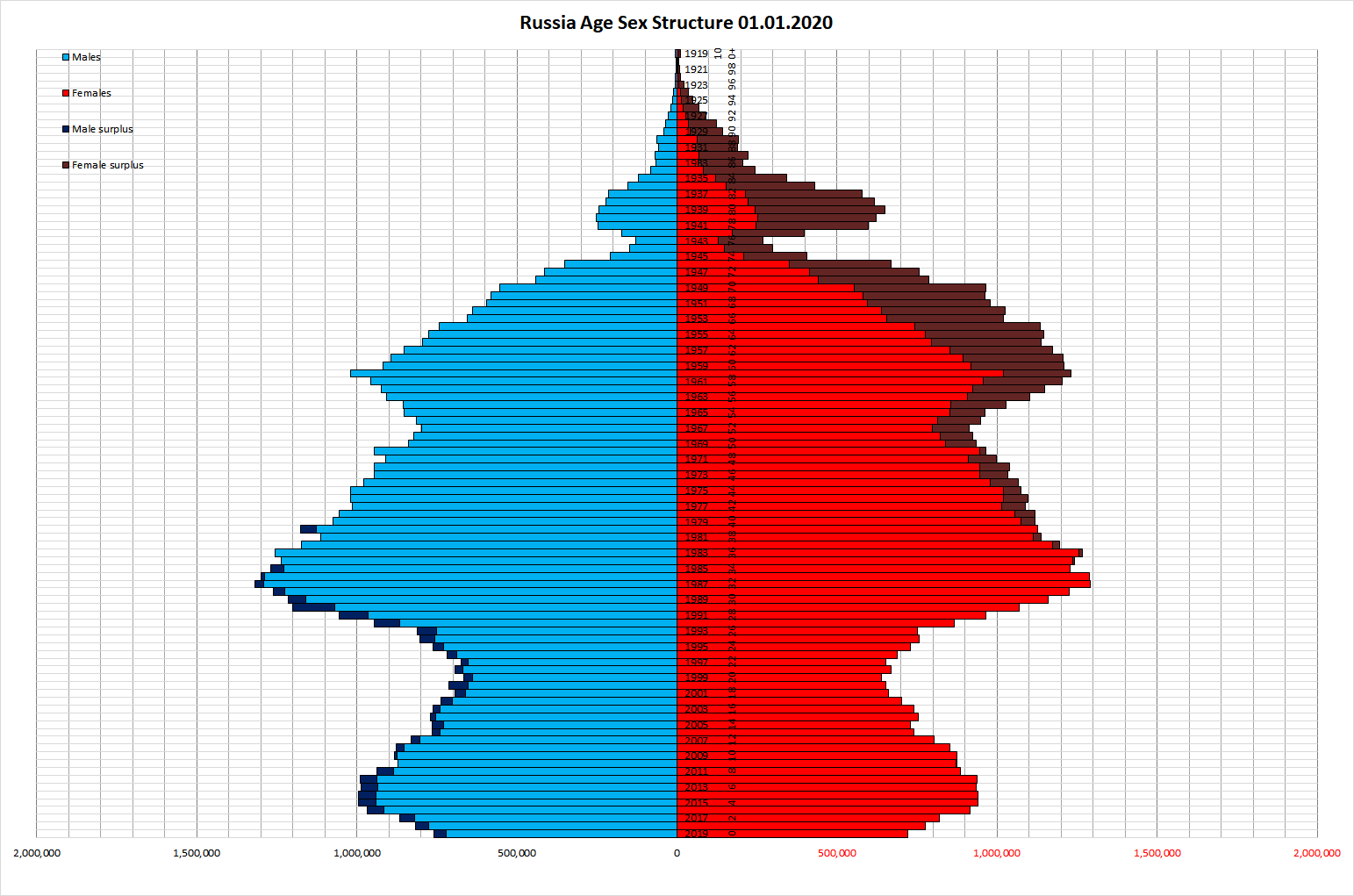

Although you may know about the Black Death (bubonic plague) pandemic of the Dark Ages, you may be surprised to learn how it shaped human thought, society, economics and even our genome into the world we participate in today. Losing large amounts of a population has long-term effects on the survivors and the descendants of the decimated society. Even modern day Russia's suffers from a cyclical effect on its birth rates from its population loss during World War II.[1]

However numbers and statistics do not really convey how the Black Death apocalypse affected people. The emotional and psychological toll it took on the survivors and descendants may have led to the birth modern Western democracy and philosophy. It may have invisibly shaped the collective memory of Europe and the Americas for hundreds of years, as Carlin argues:

“The essence of that account is of an epidemic destroying the very bonds of human society... And if parents abandoning children wasn’t destabilizing enough, other support elements in society were shattered by the justifiable fear of the pestilence. The natural human inclination to seek companionship and support from one’s neighbors was short-circuited. No one wanted to catch whatever was killing everybody.

Unlike today, when many religious groups had set up online services during the 2020 COVID lockdowns, the 12th century European society (which was overwhelmingly religious) had no safety net (or in some cases not even a local government) outside of the church itself. Carlin explains:

The church was one of the key support pillars of that society, and the clergy played very important roles, only some of which we would call religious; they were also medical practitioners, lawyers, and notary publics. They held management positions in society and formed an entire middle level of the medieval social strata. And of course, they were indispensable for religious functions like marriages and, notably during a plague, last rites.”

In the US, both secular and religious leaders are worried about the effects of declining church attendance on American society. This was only accelerated during the lockdowns as some people never returned to church once in-person services were resumed. Bob Smietana the author of Reorganizing Religion: The Reshaping of the American Church and Why it Matters notes:

Organized religion—and churches in particular, at least in the United States—are like [a] wall. They’re an integral part of the structure that holds our culture together. If organized religion continues to decline and nothing replaces it, then the roof caves in. And we can’t wait until the load-bearing wall is gone to start thinking about what will replace it.”

The 21st century church is positioned similarly to the 12th century church. During the Black Death, trust in the institution of the Church fell precipitously, like it has today. Carlin continues:

“Before the epidemic, members of the clergy had devoted their whole lives to the church. The people who replaced [the clergy that were wiped out by the plague] weren’t necessarily as committed or as educated. Corruption began to creep in, especially as men attained elevated positions in the church due to money changing hands, not thanks to their lifelong commitment or qualifications. Over the course of around two centuries, the clergy’s reputation diminished, tarnished by abuses and excess and a lack of high standards”

Some historians argue that the Enlightenment period may have been helped along by the peasant class gaining power through inheriting the abandoned land and power vacuums left by victims of the plague or rejected religious institutions. On the other hand it just as well could have been brought about by the explosion of cheap book and paper-making technologies. In Paper: Paging Through History the author, Mark Kurlansky, makes a strong case for European society being altered more by ideas than by calamity:

Fifteenth-century Europe, bursting with its own ideas, required a method of disseminating them that was faster and more immediate than the slow process of dictating to scribes. Printing proved to be that method; it freed up scientists, artists, thinkers—blossoming European geniuses—from the tyranny of their dependence on scribes

If you were to pick an average citizen from the fledgling 18th-century America who has escaped religious persecution in Europe for their (often radical) beliefs--or even a 1950s white evangelical--to time travel with you to 2030, chances are they would be shocked by a desolated world. To them it would be a cultural and spiritual apocalypse. To us it's just a normal day in the USA.

The Present Repeats The Past

Apocalypses are not just the mass deaths of people and religious institutions. We see similar patterns of apocalyptic upheaval in the political, scientific, and technological realms occuring right now. Between the end of World War II and the start of the Cold War in 1945, an apocalypse of government occurred. Although the Bolshevik revolution in 1917 kicked off a familiar cycle of the end of one empire with the start of another, the atomic bomb changed what it meant to be an empire in the modern world. Carlin writes:

One of the side effects of the bomb—it changed the American constitutional system. “Lodging ‘the fate of the world’ on one man,” Wills argues, “with no constitutional check on his actions, caused a violent break in our whole governmental system.” But it was a development that “was accepted under the impression that technology imposed it as a harsh necessity.” How, for example, would a president have time to consult with other leaders or branches of government if the enemy’s missiles were already in the air?

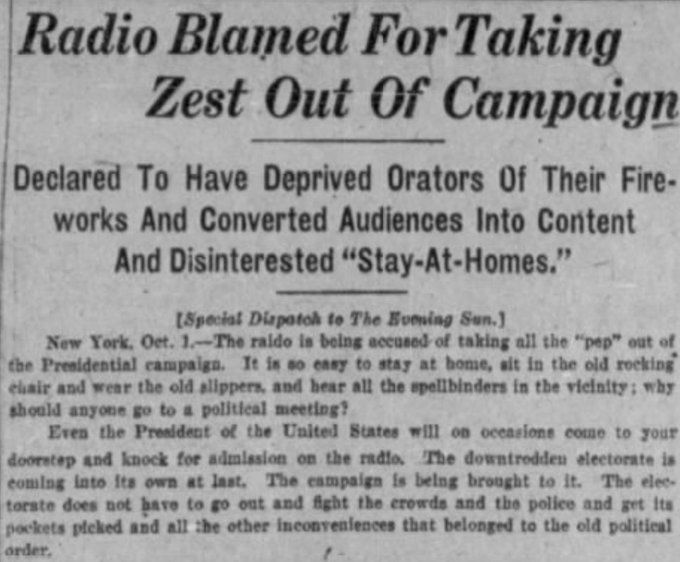

With the rise of mobile phones and global internet access in the 2010s, social media practically wiped out the television and print news industries. Although you can still (sometimes) buy a paper and catch cable news today, the vast majority of consumers consume their news online from Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, Google, and Reddit. Print shops are closing every year. As news became paid for by advertisers instead of subscribers, journalists became click-bait writers and "traditional" journalism, like the paper mills, disappeared within a decade.

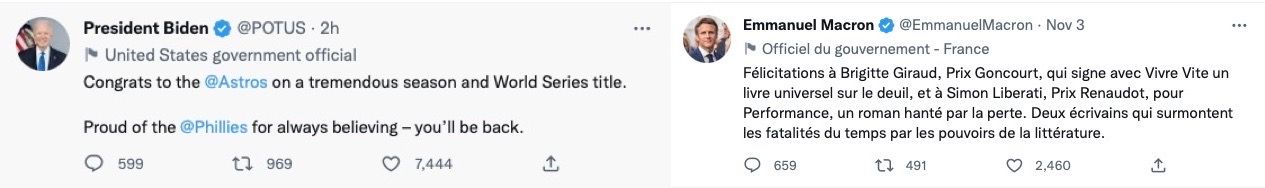

Just fifteen years ago, presidents and prime ministers primarily interacted with the public via national TV and press releases. Today, American president Joseph Biden, French president Emanual Macron, and dozens of other world leaders make announcements, congratulate sports teams, and interact on geopolitical topics and policy issues online. Within a decade, national addresses on TV disappeared and were replaced by direct announcements to constituents and the traditional media on social media.

Much of the conflict the Republican voters created in 2020 when they lost the presidential election (and several others) stemmed from echo chambers established by social media. In some ways it repeats the confusion between voters during the 1960 Kennedy-Nixon debate, where radio listeners thought Nixon had won, but television watchers felt that Kennedy was the stronger candidate. The chaos that ensued from that first televised presidential debate changed American politics forever.

Fast-forward exactly 60 years to the 2020 election and similar confusion abounded depending on whether voters were active Twitter users (at least those not stuck in the Republican echo chamber) or Facebook users who shared enormous amounts of amplified pro-Republican misinformation directly to their friends and family. "Classical" election coverage culminated in a tipping point between 2016 and 2020, causing an apocalypse in the political information sphere and changing it forever.

The Future Will Be Predicted By The Past

If social media caused an apocalypse of print, TV, and elections--and if paper and the Black Plague changed politics, the human genome, and religion--then what can we expect from future apocalypses? Although predicting future events is not this publication's specialty, we can look to the past for clues as to when an apocalypse may hit us, allowing us to prepare as best we can.

For example, In 1903, the New York Times predicted that airplanes would take 10 million years to develop. Then just nine weeks later, the Wright Brothers achieved manned flight. Twelve years later, airplanes were used to fight battles in World War I. The 20th century was filled with rapid change, new inventions, and dismissive critics who were often wrong. Whenever loud cynicism is voiced about a new technology, there's a good chance an apocalypse is waiting just around the corner should that technology succeed.

One indicator of an impending apocalypse is a sudden and rapid change in economics, technology, power, or politics. Headwinds across those three spectrums are present in every historical apocalypse, and there's no reason to doubt they'll cause the next one. After all, barbarians defeated Rome before its citizens could react, TV defeated an incumbent vice president, radio killed political campaign stumping, and online music killed CDs.

One of the most salient examples of rapid progress after much stagnation is the mind-boggling speed of AI generated artwork and its ripple effects. On an episode of Cortex, a podcast where two creators discuss their working lives, one show host notes that from his perspective, in just a few weeks AI art went from being a technology that needed hundreds of powerful server computers to something he could run on his personal computer.

With photo-realistic AI art technology now available to anyone with a computer, we may never be able to believe what we see online again. It brings enormous ramifications to politics, war, history, pop culture, and social media. We already struggle with fake news and easily-detectable photoshopped images; less-detectable AI "photographs" will lead us into quite an apocalpyse over the coming years.

Other areas of rapid change we should be on the lookout for are the centralizing and decentralizing trends in politics, the relationship between politics and technology, and wealth inequality. Balaji S. Srinivasan in an interview on Making Sense, a podcast by Sam Harris, makes some apocalyptic observations about western countries. What he calls "start-up countries," as well as India and China, are countries poised to create potentially devastating shifts (for the West) in geopolitics and power over the next three decades due to their embracing of different styles of governing, or the normalization of radically new technologies in their citizens lives before Western governments figure out how permit or use them.

Many predicted apocalypses by 21st century technologists and technology enthusiasts are yet to be seen. Cars aren't fully self-driving, Bitcoin may not kill banks, and Mastodon may not kill Twitter. Yet the country of Salvador adopted Bitcoin as legal tender, social networks come and go, and electric cars sales have never been higher. The future dawdles for seemingly forever, but then sometimes its apocalyptic effects happen all at once.

Links of Interest

The End Is Always Near: Apocalyptic Moments, from the Bronze Age Collapse to Nuclear Near Misses by Dan Carlin (Book, affiliate link)

Reorganized Religion: The Reshaping of the American Church and Why It Matters by Bob Smietana (Book, affiliate link)

Paper: Paging Through History by Mark Kurlansky (Book, affiliate link)

No, the Black Death Did Not Cause the Renaissance

How The Black Death Built The Modern West

What does a nuclear bomb sound like? (Video)

#134: AI Art Will Make Marionettes Of Us All Before It Destroys The World (Podcast)

#133: The Ethics of AI Art (Podcast)

With Stable Diffusion, you may never believe what you see online again

MIT Prediction of Civilization Collapse Appears To Be On Track

Some economists and demographics experts argue that the deaths in WWII, while impactful, are not solely responsible for the cyclical fall in birthrates, so much as the cyclical crises that have impacted the USSR (such as its fall and breakup) have been. ↩︎